Competency frameworks are a critical feature of learner-centered schools and education systems. Competency frameworks help bring a 30,000-foot vision for learner outcomes to ground zero. They define a set of important capabilities (e.g., reading critically, designing solutions, sustaining wellness) for college and career, civic engagement, and lifelong learning.

In a fully developed competency framework, each competency is deconstructed into a set of component skills or processes, and includes the equivalent of a developmental rubric or “continuum” that describes—to the best of our knowledge—the specific, observable ways in which these important skills develop from novice to expert.

By design, a competency framework enables us to answer these mission-critical questions:

Over the years, our team at reDesign has had the privilege of leading or supporting the design of many competency frameworks, working with progressive schools like Crosstown High School, Marin Academy, and Singapore American School, as well as multiple district and state departments leading innovation in this space through incubator and innovation networks, such as those of the Office of Personalized Learning, South Carolina Department of Education, and the Idaho Mastery Education Network.

We are constantly reflecting on and refining our competency framework design practice, and over the last ten years our work has evolved in significant ways. In this post, I synthesize five big ideas for learner-centered competency framework design, along with a set of question prompts that can serve as equity filters related to each big idea. These five big ideas are:

We’ve learned the power of approaching competency framework design as though you were a community organizer, not just a technical writer. What do your stakeholders envision will be true for every learner when they leave your institution or program? What is the common denominator of a truly equitable education that will prepare young people for the demands and opportunities of our rapidly changing world?

Start here. This is the first question to grapple with as a community. If your competency framework looks like power standards dressed up with some cherry-red lipstick (which I happen to love, though I’ve never worn), I’d say come back to the drawing board. Standards were created to provide important guidance on subject-specific knowledge, concepts, and skills.

In this way, standards work in partnership with a competency framework. Distinct from standards, competencies define the transferable skills, strategies, and processes that are important within and across disciplines, and as I discuss later on, they include social and emotional skills and strategies that are often missing from our standards frameworks.

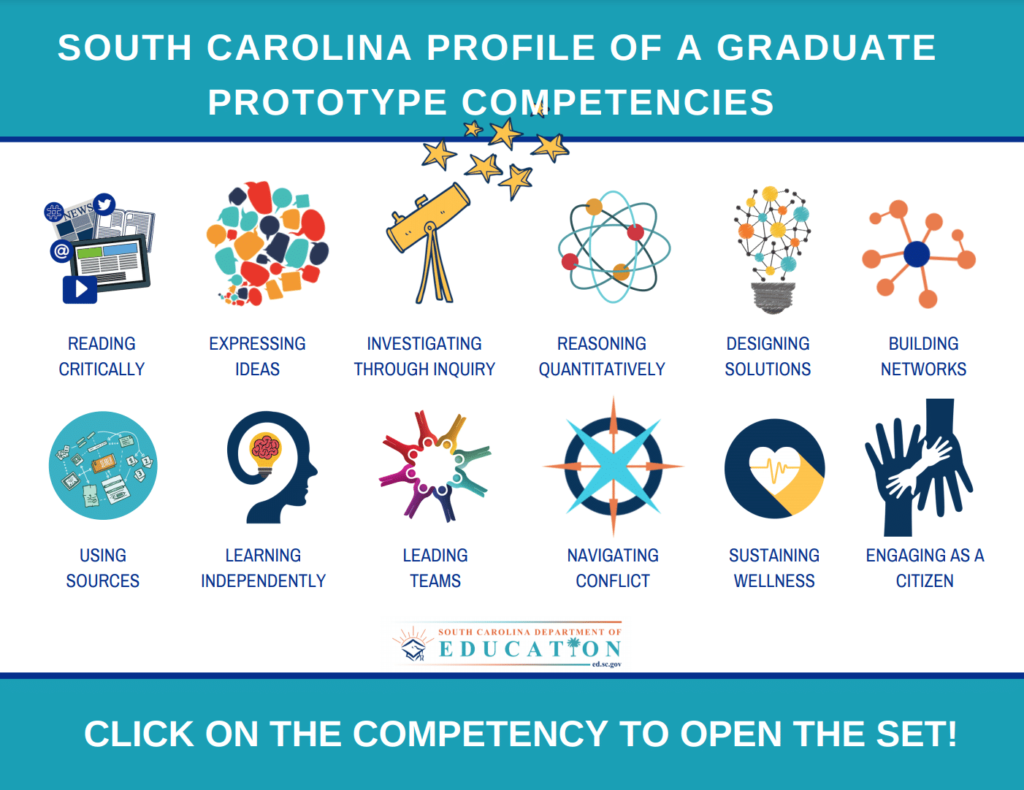

In recent years, the development of Graduate Profiles is an example of a community-driven process for articulating a shared vision that grounds competency framework design. Our friends in South Carolina modeled this approach in a powerful way. In 2013, they convened parents, policy makers, students, business leaders, community groups, and educators from across the state to help create the Profile of a South Carolina Graduate.

Four years later, when they decided to move forward with the design of what are now called the Profile of a South Carolina Graduate Competencies, they once again convened another diverse stakeholder group to work alongside our team at reDesign. They unpacked their Profile for us and shared what it meant to them. They examined and critiqued competency frameworks from the field that we had curated, and gave us warm and cool feedback on these examples. They reflected on and responded to career readiness research and job forecasting data. They gave us really good advice to hold onto as we designed, like:

They engaged in close readings of drafts, and provided detailed feedback. In short, they were deeply engaged and helped shape the design in their vision. The Profile of a South Carolina Graduate Prototype Competencies would not have come to fruition without their vision, input, engagement, and support all along the way.

A second way that we’ve learned to center learners in the design of a competency framework is to apply an equity lens to the research process, asking questions in line with the needs and experiences of the young people for whom we’re designing, and always holding in mind the broader racial, historical, and economic context that helps explain how we got to an education system with such inequitable access and disparate outcomes.

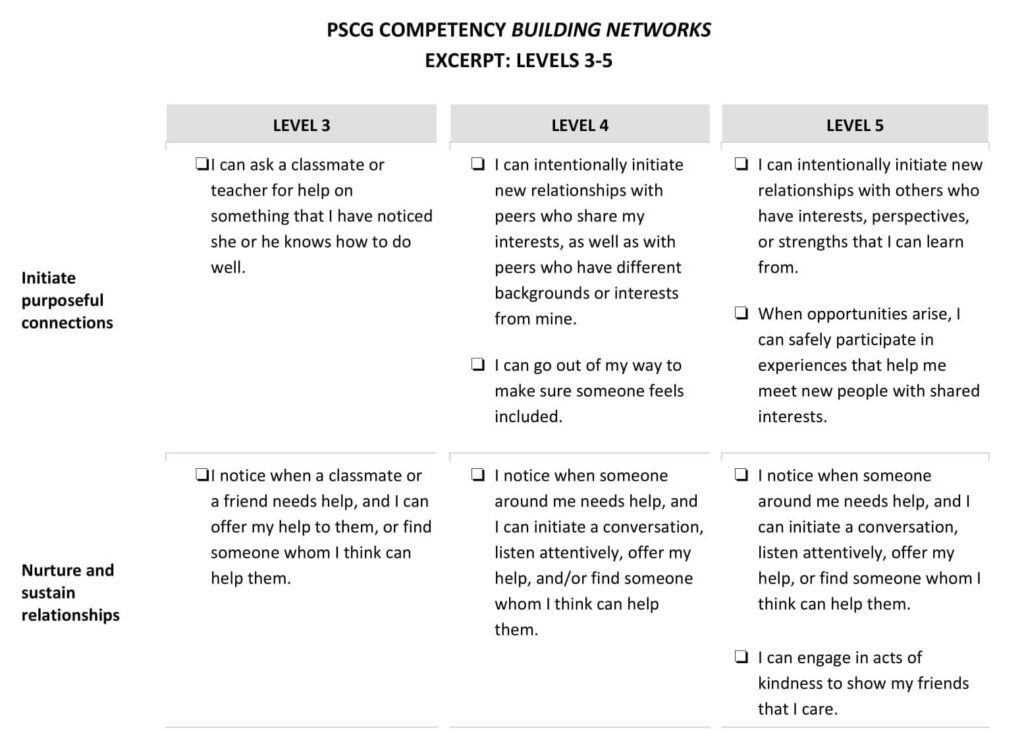

For example, instead of primarily asking, “What does the research say about college readiness skills?,” we included questions like: Which factors most impact children’s economic mobility in the United States? We learned that one of five major factors that correlate with upward mobility is greater social capital (Raj, 2014), which helped inspire and inform the design of our Building Networks competency.

Other more recent studies, such as The Brookings Institution How We Rise study (2021), further build the case for Building Networks competency development from an equity perspective: they found that race was one of the most important and consistent differentiators of social networks, with Black males’ networks being consistently smaller and less strong than those of peers.

From a change leadership perspective, this competency supports students by making transparent the skills and strategies involved in building and sustaining relational networks. It also helps reshape the system, by creating a “reinforcing structure” that sets the expectation for instructional teams that learners will have opportunities to authentically practice and develop the skills of Building Networks.

Equity-focused research might also lead you to look beyond traditional, white- and male-dominated academic sources, or to the design of competencies that focus on nurturing and sustaining cultural identities. We often encourage folks who are involved in a collaborative competency framework design process with us to “tap their own lived experience” as an important source of inspiration and ideas.

It was this process that inspired the competency, Develop and Sustain Self-Knowledge, Wellness, and Self-love, for one of our partner schools, that includes such skills as explore my cultural and social identity, engage and disrupt internalized forms of oppression, and express my identity through activism to advance social justice. I remember thinking that, as a white woman, I simply didn’t have the cultural perspective or lived experience needed to design a competency like this. Another reminder of the power and importance of representation.

We believe centering learners in our designs also means attending to the whole child, not just to that which is traditionally held as “academic.” We now know how profoundly our social and cultural contexts shape our ability to learn. When we must, we might categorize along the lines of “academic” and “efficacy” competencies. Efficacy competencies, like Navigating Conflict, Sustaining Wellness, Building Networks, and Leading Teams—all competencies we had the opportunity to create for the Profile of a South Carolina Graduate (PSCG) Competency Set—emphasize the important social-emotional and interpersonal skills that are critical to well-being.

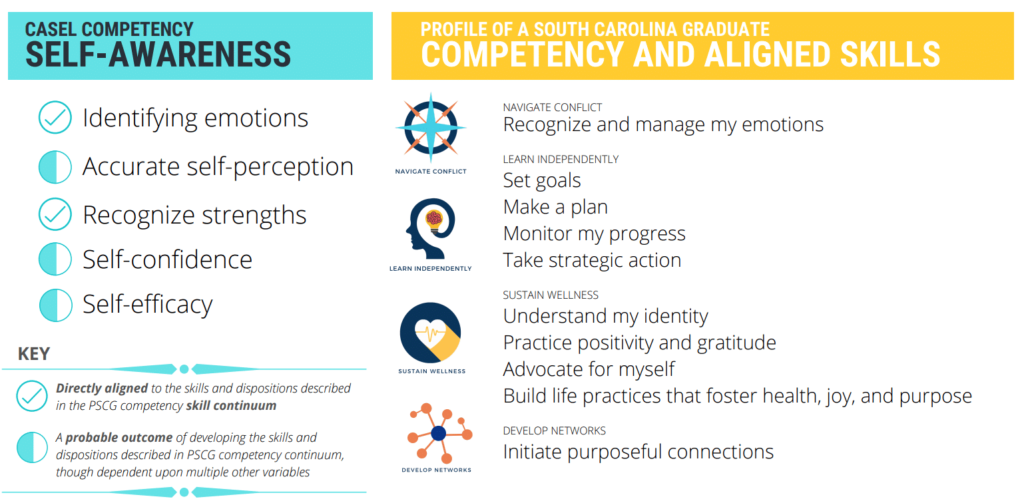

Recently, we worked with the Office of Personalized Learning at the South Carolina department of education to develop a crosswalk between the Profile of a South Carolina Graduate (PSCG) competencies and the CASEL competencies. We began by examining the descriptors for each of the CASEL Competencies, noticing which of these were truly skills or practices within the locus of learner’s control (e.g., perspective-taking, stress management, goal-setting), and which of these were better classified as outcomes shaped by many factors, some beyond learner’s control (e.g., self-esteem, self-confidence).

Next, for those identified as skills or practices, we identified PSCG competencies that had explicit connections, such that teachers could use the PSCG skill continuums to support explicit instruction and progress monitoring for learners around the CASEL competencies. Finally, we pulled it all together in this Infographic. In the example below, you can see that indicators of the Self-Awareness CASEL Competency are crosswalked to multiple skills from four different PSCG Competencies: Navigate Conflict, Learn independently, Sustain Wellness, and Build Networks.

Our learning has brought us to a strong preference for transdisciplinary competency frameworks, instead of those organized by subject areas. This won’t be news to you: Reading isn’t just an “ELA” competency. Inquiry isn’t just a “science” competency. Reasoning Quantitatively isn’t just a “math” competency. Competencies, by definition, are transferable skills that have importance and utility in multiple contexts.

While there is an important place for discipline-specific content and skills, a competency framework that articulates a distilled set of transferable skill sets can help unify an instructional program, and calibrate instructional teams across subject areas and grade levels. It becomes the backbone of the academic program. Decoupled from disciplinary content, transdisciplinary competencies provide a flexible structure for recursive skill development opportunities and longitudinal growth measurement.

In the age of COVID, reduced instructional time, and hybrid learning environments, a competency framework can be a game-changer because it:

Competency frameworks can also help us break from time-based, grade-bound learning expectations that have no basis in the learning sciences. It is not a radical idea to replace grade-level expectations with developmental progressions. It is an evidence-based idea.

In a competency-based learning system, we can embrace reality: every learner is at a unique place in their journey. As educators, our prerogative is to meet learners where they are. What if we moved beyond proficiency-based scales built around a grade-level standard, that expend so much of educators’ precious time in the work of creating language and levels for evaluation and grading, not learning? What if we moved toward competency-based progressions that span the pre-K to professional continuum, that provide specific, observable, student-friendly language for each developmental milestone along the way?

It is time to embrace a developmental approach to articulating learning outcomes. If we do this, we will begin to reorient our diagnostic tools and structures, our practices, and our culture to a focus on growth, learning, and embracing learners where they are.

Learn More

This article was originally published by Aurora Institute’s CompetencyWorks Blog.